The Journey towards Restoration

In the quest to restore damaged and degraded coral reefs, Dr Anjani Ganase and her team have undertaken an approach to research reef types and to allow, as far as possible, nature’s process to lead the way.

The first time that I observed coral spawning was in Curaçao in 2010 during my Master’s research internship. My dive buddy and I - both Master’s candidates at the CARMABI Research Station - were invited to join a team collecting sperm and eggs from Elkhorn corals. Although coral spawning had been observed since the 1980s, scientists were still figuring out the best methods for culturing coral larvae in the lab in order to study the early life history of coral species and for the purpose of coral restoration. Coral spawning refers to the release of coral gametes (sperm and eggs) of the corals into the water column where they mix and fertilize. The coral larvae form and swim down to the reef to settle and grow. This happens seasonally timed by environmental cues.

As a casual observer, I wasn’t sure what to look for and was distracted by many other organisms creeping around in the dark. Suddenly there were tiny pink bundles (sperm/ egg bundles) drifting around us and many nets were cast over the branching colonies to capture for fertilization in the lab. It was a night to remember! At that time, I never thought that I would be attempting to do this 13 years later. In 2022, the person I needed to call was my dive buddy, Dr Valerie Chamberland, who is now a lead researcher at SECORE International studying the reproductive patterns of corals in the Caribbean for the purpose of enhancing restoration.

Divers

descending at sunset. Photo by Anjani Ganase

Coral Reefs of Trinidad and Tobago

When I returned to Trinidad and Tobago, I realised that we urgently needed to care for our coral reefs that were allowed to degrade out of sight out of mind. Firstly, Trinbagonians needed to see what coral reefs of Tobago look like and to be educated on how we impact corals and how this affects our lifestyles. This research became the Maritime Ocean Collection (maritimeoceancollection.com) a platform to view coral reefs of Tobago in an immersive Google Street View mode. Secondly, we needed to prepare ourselves for a future of climate change with projections of severe coral bleaching events and disease outbreaks that will drive coral mortality as the global ocean warms. To do this, Tobago needs to build it capacity in coral restoration. We had lots to learn from our Caribbean neighbours.

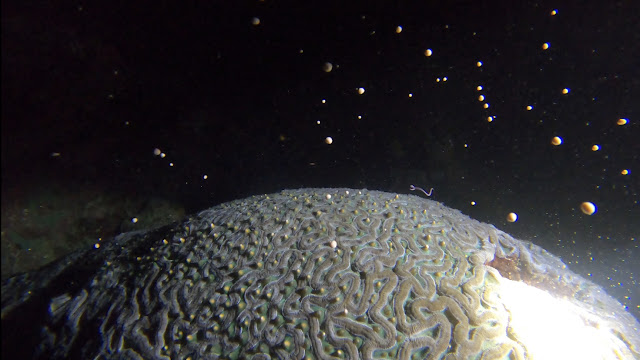

Unlike the common forms of coral restoration that rely on coral farming and the use of coral clones to rebuild the reef, we need to build resilience through genetic mixing as much as possible. There are several modes of sexual reproduction that corals use but about 75 % of the coral species carry out broadcast spawning which is an annual event where corals synchronously release massive amounts of sperm and eggs in the water column. Coral larvae propagation (growing new corals from enhanced methods of fertilisation and settlement) as a method of restoration aims to improve the fertilisation success of the spawning event; these coral babies will have unique genetic combinations (diversity) and will be better able to adapt to a future of unknown disturbances.

Brain

coral releasing sperm and egg bundles during spawning. Photo by Anjani Ganase

Corals

prepare to release the sperm and egg bundles in a process called setting. Photo

by Hannah Lochan

2022 Spawning in Tobago

Before we begin coral propagation, the team at the Institute of Marine Affairs set out to learn when coral spawn in Tobago. This has been observed by the casual diver but not studied. The timing of coral spawning is dependent on several environmental conditions. Corals tend to spawn in the warmer months of the year; these months shift based on where you are geographically. The corals then synchronise their spawning based on the full moon and sunset. Different species may have different windows of spawning which is essential to maximise fertilisation success.

To monitor coral spawning, the ideal strategy is to monitor as often as possible over several months. This means going underwater for many nights after full moon; and monitoring as many sites as possible. A small team of four or five divers mapping the first impressions of coral spawning in Tobago required a total of over 600 hours underwater observing corals for up to ten nights after full moon over four months. We were able to monitor two sites. The shallow dives allowed us to be underwater for over an hour at a time swimming back and forth along sections of the reef scanning the corals to see if they were readying themselves to release the sperm and egg bundles.

Time ticks by slowly on a quiet night and the cold seeps in quickly. As you cruise by, you become familiar with the reef residents surprised by the light of your torch. The sleeping parrotfish in its bubble of mucus, the basket star that crawls to its perch as the sun sets, the lobsters and crabs that crawl out of their crevices. When spawning begins, the coldness gives way to a rush of excitement. There is a mad dash to find the source of the spawning by following the trail of bundles in the dark.

On some colonies, you actually see the coral polyps prepare to release the gamete bundles as they hold the bundles in the openings of their polyps, this is called setting. The time between the setting and the final release of the bundles into the column can go quickly but sometimes it feels like forever. Don’t blink or move your eyes away for a second, you might miss it, this happens often. We had a lot to learn which included keeping calm and not wasting precious air with excited swimming. Divers either surfaced with lots of chatter or without saying a word revealing the type of dive they’ve just had.

We observed several species of brain and massive coral. We were surprised by spawning of other organisms, such as the mat tunicates that overgrow several parts of the reef as well as soft coral – sea plumes. However, the journey to thoroughly understanding the patterns of spawning in Tobago has only just begun. The first spawning season has answered some questions which lead to many more questions. While some coral species aligned precisely with the spawning times of the species in other areas of Southern Caribbean, we didn’t see other common species of coral spawn at all.

In this new year, there will be more opportunities to observe coral spawning and move closer to successful coral restoration in Tobago. This is the nature of research. When your field is the ocean, it is even more exciting with great rewards. We look forward to this year’s coral babies.