Exploring Kick'em Jenny Volcano

The Caribbean archipelago is a chain of small islands in a vast deep ocean. Here Dr. Diva Amon explores the underwater volcano, Kick’em Jenny, off Grenada. Dr. Amon is a deep-sea biologist with experience in chemosynthetic habitats and human impacts on the deep sea. You can find out more via her Twitter (https://twitter.com/DivaAmon) and her website (https://divaamon.com/).

The Kick’em Jenny (KEJ) volcano first rumbled into the public eye on July 23, 1939, when it shot a cloud of steam and debris 275m up into the air, and sent 2-metre tsunamis to the shores of Grenada, the Grenadines and Barbados. While KEJ may be a looming threat to us here in Trinidad and Tobago, we usually fail to look past that, never stopping to ponder what strange environments and animals may lurk beneath the Grenadian seas down on the slopes of the volcano.

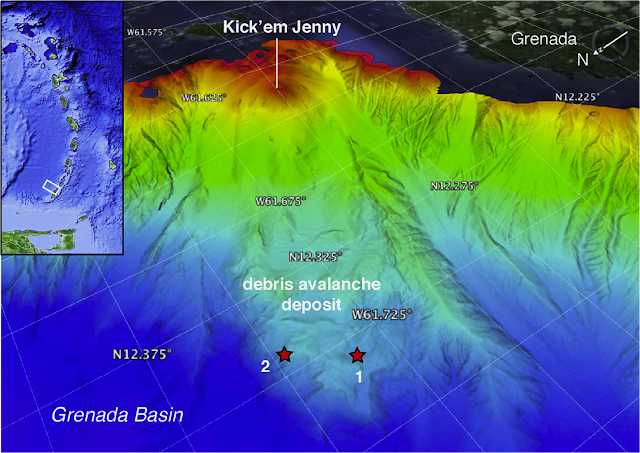

KEJ is the only active submarine volcano in the Caribbean, created by the subduction of the Atlantic Plate below the Caribbean Plate, and is located just 9km north of Grenada. It is also the most active volcano in the Caribbean, with thirteen eruptions since 1939, including one that recently caused a large portion of the volcanic cone to collapse. Because of the risk that KEJ poses to the southern Caribbean, it is monitored frequently, resulting in very detailed maps. These show a 1300m-high cone with its summit at only 190 m depth (within the reach of SCUBA divers!) sitting on the edge of the continental slope. While the crater was briefly investigated by NOAA using a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) in 2003, it wasn't until 2013 and 2014, during expeditions by the E/V Nautilus, that any exploration deeper than the crater was undertaken.

The findings of this ROV exploration were extraordinary! We discovered completely unknown habitats: ten cold seeps with chemosynthetic communities along the debris slope below the collapsed volcano between depths of 1800m and 2100m! Amazingly, these are the first cold seeps found off Grenada and only the fourth in the southern Caribbean. Cold seeps are special deep-sea environments where bacteria use chemical energy from hydrocarbon fluids seeping from the seafloor to make food, a process known as chemosynthesis. These bacteria can be found inside or on the surfaces of animals, or growing in thick mats on the seafloor, and are the basis of the food chain at cold seeps, like plants are on land and in shallow waters. Cold seeps are unique because they have a plentiful food source (bacteria) so animals living there can grow to large sizes rapidly and reproduce quickly, unlike in the rest of the deep sea which is very food limited. As a result, cold seeps are oases of life filled with numerous endemic and interesting animals, with the KEJ seeps being no exception!

The KEJ seeps occur on steep slopes and appear as dark and white intertwining streams flowing downslope. The dark colour is reduced sediment and the white colour is the bacterial mats. These are areas where methane-rich fluid seeps out of the sediment and as a result, this is where the animals live! Unlike the Trinidad and Tobago seeps, which were roughly the size of football pitches, these are only a few metres across, and are inhabited by white chemosynthetic clams, pink sea cucumbers, and tiny brittle stars. The most conspicuous animal at the KEJ seeps is a species of mussel named Bathymodiolus boomerang, so named because the shell has a kink similar to that of a boomerang. These mussels are truly enormous with the largest documented mussel, measuring 36.6cm, discovered here. These mussels also house a stowaway: hiding within each is a two-inch worm covered in scales, a relationship we have yet to understand! Even though there were many species never seen before, there were also some overlapping with species seen at the Trinidad and Tobago seeps: snails, white shrimp, spiny crabs, metre-long tubeworms, and tiny white fan worms in bushels.

The fact that there are species shared between the KEJ seeps and the Trinidad and Tobago seeps sheds light on the dispersal and colonisation of cold seeps over large distances. The KEJ seeps may act as an important stepping stone for the movement of seep species between Trinidad and Tobago and the Gulf of Mexico. Findings seeps in this geologic setting was also unusual and is likely due to the burial of organic matter by the catastrophic collapse of the volcano some years ago. The organic matter in this high-pressure environment decomposed without oxygen leading to the creation of sulfides and methane that “flow” downslope providing energy for these unique communities. This leads us to believe that seeps and their chemosynthetic inhabitants may be more common worldwide than previously thought. Excitingly, we also suspect that many of the species discovered here are new to science but this can only be confirmed with further research.

Our work to understand the KEJ cold seeps and their inhabitants is only just beginning but the discovery of these sites is already provided tantalizing insights. These discoveries are yet another reminder of how little we know about the deep sea, especially here in the Caribbean. It is only by exploring the depths of the region that we can begin to understand what habitats and species exist, and how best we can work towards their preservation.