Saving Buccoo, Saving Trinidad and Tobago

Anjani Ganase, marine

scientist and PhD candidate for a study of Coral Reefs, made a presentation to

the Green Market community in Santa Cruz. She shares the presentation here in

support of her belief that caring for the Caribbean Sea no longer rests only with

marine scientists. We should all know and care about what’s happening offshore

our islands and in the oceans everywhere.

This feature was first published in the Tobago Newsday on Friday March 3, 2017

This feature was first published in the Tobago Newsday on Friday March 3, 2017

Follow Anjani on

twitter @AnjGanase

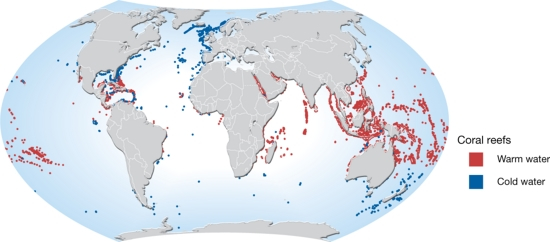

Coral reefs around the world can be found in specific locations,

around tropical islands where ocean temperatures are warm and the water is

generally clear enough for sunlight to filter through. These locations amount

to about one percent of the ocean floor. If we look at the map, we’ll see that

our islands – Trinidad and Tobago – lie within one of these coral-select

regions of the world, the Caribbean.

|

| Map shows where most coral reefs are located (Courtesy WWF) |

According to the experts: “Coral reefs are a

critical global ecosystem. They support 25% of all marine life worldwide, and

are estimated to have a conservative value of $1 trillion, generating $300-400

billion each year in terms of food and livelihoods from tourism, fisheries, and

medicines” (WWF 2015, Smithsonian Institute).

Coral reefs are important in the life

cycles of many of the species that we harvest from the sea. They are important

income generators in food and tourism industries to coastal communities.

However, coral reefs around the world are

polluted by what runs off the land. They are further stressed by rising ocean

temperatures. Extreme rises in water

temperature result in the stark bone white forms, a condition that’s known as

bleaching. If you thought that the natural healthy state for reefs is white,

you are wrong. Coral communities that are alive and growing are as colourful as

vegetation in a rainforest. Coral reefs have been compared with rainforests, both

essential to the health of the planet. Today, we are in the midst of a

bleaching event that may not be easily reversed, even if humans come together

to clean up the pollution (chemicals, plastics, garbage, sewage, silt) that ends up in the

ocean; and to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide that is emitted into the

atmosphere by agricultural, industrial and human life practices.

Let’s pause here to understand how

carbon dioxide and other emissions change the earth’s ecosystem. All animals

breathe out carbon dioxide. Factories, burning fossil fuels, releasing fossil

fuels (oil, gas, coal) from reservoirs in the earth, transportation systems

based on fossil fuels, all result in increases in carbon emissions. At the same

time, changes such as enormous gyres of trash in the Pacific and Atlantic

oceans, chemical pollution, over-fishing, rising temperatures, coastal

development, are altering the capacity of ocean ecosystems to absorb carbon.

Humans also affect the ocean through

unregulated and indiscriminate fishing. Most of the large species – whales,

sharks, bigger fish like tuna, wahoo and grouper, and sea turtles – have been

severely depleted. Food fish are smaller and further down the food chain.

Herbivores, for example parrotfish and others that graze on the reefs, have

also been fished out. If you have a look at Buccoo Reef today, you’ll see

mainly small fish.

Coral reefs have been compared to “the

canaries in the mines” a term that suggests they are indicators of the health

of the oceans, and of planet earth.

BRINGING AWARENESS TO THE STATE OF OUR

SEAS

While most of humanity, land-based and

oblivious to what is happening in the seas, has proceeded with “business as

usual,” some are aware and warning about the peril to the planet, raising

issues like climate change and its connection to consumerism, carbon release in

the atmosphere and warming global temperatures, over-population, pandemics and

the growing pressures to support human life.

Organisations and groups promoting

change include the IPCC (Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change), Mission

Blue, and the Global Change Institute of the University of Queensland in

Australia among others. We urgently need more individuals and communities around

the world to identify with the cause of a safe and healthy planet.

I’ve always identified with the sea and

see myself as an island person. I was born and lived in Trinidad and Tobago until

I went to university, and cemented my relationship with other campaigners for

the health of the oceans. It was a “round the world route” that brought me to the

Global Change Institute and its significant project, the XL Catlin Seaview

Survey. This was a long way from the poultry farm in the Northern Range valley

of Santa Cruz, with recreational visits and vacations at the beach.

In high school, I loved swimming and represented

the red white and black on the Carifta teams and in water polo. Curiosity about

waterways (Santa Cruz and Caroni rivers, the Nariva swamp and all beaches and shorelines)

took me to Tobago (from Charlotteville to Sandy Point) with my family. At

university, I delved into the study of marine organisms. I learned to snorkel and scuba dive in waters

around Trinidad and Tobago. After a first degree, I returned to a research

project on sea turtles in Tobago.

The master’s programme in marine

biology at the University of Amsterdam, took me to the associated research

institute CARMABI in Curaçao where I worked with teams monitoring the coral

reefs. Through the University of Amsterdam came a research project on Heron

Island in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef; which led to a relationship with the

Global Change Institute. I was one of the first divers trained to operate the

new underwater photographic equipment developed to capture images of

ocean-scape, in particular the shallow coral reefs. I later accepted the offer

to pursue PhD study at the University of Queensland.

|

| The underwater camera developed for the XL Catlin Seaview Survey records images in a 360 degree array. Photo courtesy The Ocean Agency/ XL Catlin Seaview Survey |

The XL Catlin Seaview Survey brought

academics from the University of Queensland, communications and advertising and

commercial interests, together with computer tech giants like Google, in a

project to map coral reefs. The 2013 Caribbean Expedition recorded reefscapes

along the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef and selected islands in the Caribbean. That

programme has provided thousands of images and videos of these reefscapes which

are available for public information through the webpage globalreefrecord.org

SAVING CORAL REEFS IN STRATEGIC PLACES

Information is the first step to

dealing with climate change. The next new initiative of the Global Change

Institute and The Ocean Agency, is “to identify and prioritize protection

efforts on the coral reefs that are least vulnerable to climate change, and

also have the greatest capacity to repopulate other reefs over time. Our aim is

to catalyze the global action and investment necessary to save this critical

ecosystem.”

The project is called 50 Reefs. Over the next months, 50 Reefs will identify what Sylvia Earle calls “hope spots” around the world.

According to the 50 Reefs webpage, this

initiative comes at a perilous moment for coral reefs, as current estimates indicate

that barely ten percent will survive by 2050. It is supported by a unique

philanthropic coalition of innovators in business, technology and governments, led

by Bloomberg Philanthropies with The Tiffany & Co. Foundation and

The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. The aim is to prevent the worst economic,

social, and environmental impacts of this enormous crisis. Without coral reefs,

we could lose up to a quarter of the world’s marine biodiversity; and hundreds

of millions of the world’s poorest people would lose their primary source of

food and livelihoods.

|

| A bleached coral reef in the Maldives. Photo courtesy The Ocean Agency/XL Catlin Seaview Survey |

“This

is an all hands on deck moment,” said Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Director of

the Global Change Institute. “We are establishing the first global coalition of

philanthropic, governmental and non-governmental organizations that will be

aimed at slowing the decline of the

world’s coral reefs.”

“This initiative was developed after

witnessing unimaginable loss of reefs over the last two years,” said Richard

Vevers, founder of The Ocean Agency. “Even if the targets set by the Paris

climate agreement are met, we will lose about 90 percent of our reefs by mid-century.

50 Reefs gives us hope that we can save enough of these surviving reefs to

ensure they can bounce back over time.”

The 50 Reefs plan is shaped by what the

XL Catlin Seaview Survey allowed us to see. In addition to the on-going

scientific research, there will be a strong component of communications, engaging

stakeholders and especially communities. Conservation teams will seek support

from governments and organizations to enact necessary legislation, or to

promote guidelines already in place.

In Trinidad and Tobago, we have Buccoo and other Tobago reefs that have been sources of benefit to fishing and coastal communities for at least a hundred years. Recommendations for conservation have been documented since the late 1960s and are still applicable today. The area was designated a marine protected area in the1970s but regulations and management practices remain less than adequate.

Shouldn’t Buccoo reef and marine park also be protected, to become a location for coral regeneration over the next 30 years?

|

| Coral bleaching in American Samoa in the Pacific Ocean: the photo on the left was taken in December 2014, the other in February 2015. Photo courtesy The Ocean Agency/XL Catlin Seaview Survey |

LINKS TO PROJECTS AND STRATEGIES FOR SAVING CORAL REEFS: